Name of Company Selling Metal Yard Art at Texas State Fair

Dallas has always been a transient urban center, and that lack of rootedness has ofttimes led to the misconception that information technology is a city without much history. Perhaps that is considering not many people stick around long enough to learn the history, or those who practise tend not to prove much interest in it. Ever since John Neely Bryan planted his cabin on the banks of the Trinity River, Dallas has been a city focused singularly on the unspoiled promise of the future, not the inheritance of the by. Ironically, that obsession with the new is one of its oldest and most enduring characteristics.

Dallas' transience describes not only the inhabitants of the city, but too its concrete form. One of the about remarkable aspects of this urban center'south history is how, in its relatively short 178-odd years of existence, so many neighborhoods were born, evolved, destroyed, replaced, erased once again, and remade anew once again—all in the name of striving toward some realization of Dallas' platonic grade. The consequence of this impetuous preoccupation with edifice and rebuilding is a city left with few concrete markers of a past that, though invisible, continues to shape the nowadays.

And Dallas' residents have likewise long sought to remake themselves against the properties of the mythic promise and wide-open possibilities of the American frontier. Cattle ranchers became bankers. Widowed pioneer women became industrialists. Vaudeville theater operators became civic-minded philanthropists, cotton salesmen became tech industry giants.

Dallas is where dentist Doc Holliday became a professional gambler; where Ray Charles fabricated the leap from route-weary musician to superstar; and where poor-every bit-dirt Low-era teenagers Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow fashioned themselves into fairy-tale bandits and cult heroes.

For Dallas' transient inhabitants, the land and the urban center were tools best used at the service of one's personal ambition, then it is not surprising that Dallas' urban course has too endured its own continual overhaul. The prized achievements of the past were plowed under in the proper noun of concern, progress, and a new vision of the future.

This was an illuminating, if difficult, project to put together. The discovery of Dallas' rich cultural, social, and architectural heritage was accompanied past the dejected realization that so much of that history has been lost. It was incommunicable not to experience alternatively nostalgic, sad, and even aroused when coming upon images of lost and forgotten buildings, streets, neighborhoods, shops, clubs, and eateries. It was impossible, too, not to imagine what Dallas could look like today if more respect had been shown to the achievements of previous generations. One could speculate that, had such due been paid, Dallas may take emerged a more than confident and self-bodacious metropolis. It would certainly be a more beautiful city.

But then, had this "lost city" survived, Dallas wouldn't really exist Dallas. In that sense, this is not a story of a lost identify. Rather, it is an effort to find in the vanished places of the past a new way of encountering the city Dallas has get.

Early on History

A City Founded on Hard Justice

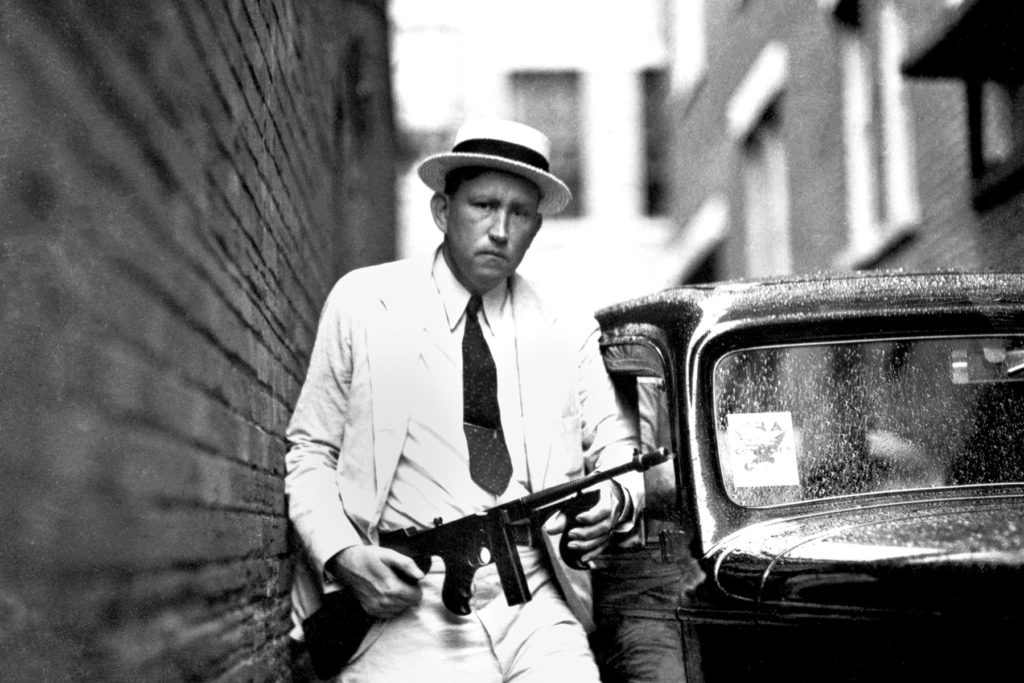

In 1856, the son of one of Dallas' founding families was caught cheating while gambling and was shot by his victim. Left without whatever recourse to enforce police and social club, Dallas' founders figured it was fourth dimension to draw upwards the metropolis'south articles of incorporation. In subsequent years, Dallas maintained its reputation for hardened justice. In the 1870s, Mayor Ben Long attempted to clean up Boggy Bayou, i of the town's cerise-light districts, which was located between Commerce Street and the present-24-hour interval convention centre. The mayor and his lawmen found themselves drawn into a three-twenty-four hour period gunfight, as obstinate gamblers barricaded themselves into a gaming house and challenged the mayor to take them out by forcefulness. By the 1930s, sheriffs like R.A. "Smoot" Schmid (pictured) almost ran the city. Smoot palled effectually with the likes of gambler Benny Binion and earned fame for his office in gunning down Bonnie and Clyde.

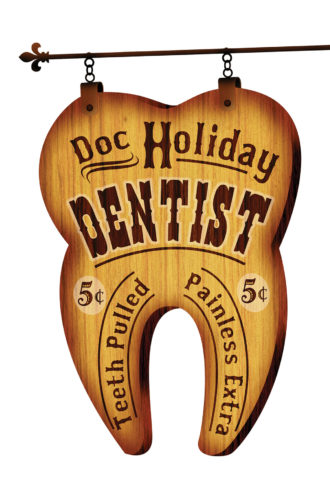

Doc Holliday Finds New Work

In the 1870s, the Dallas State Off-white & Exposition, a precursor of the State Fair of Texas, gave an award for "best prepare of golden teeth" to a young dentist newly arrived from St. Louis named John Henry "Medico" Holliday. At first, the award was a boon for Medico Holliday'due south new dental practice, which was located on Elm Street, merely east of Market Street. Just business suffered when Doc's coughing fits tipped patients to his tuberculosis.

Holliday looked for a new profession, and he found one in the Julian Bogelís Saloon. At the time, information technology was estimated that Dallas was home to more than 100 professional person gamblers. Afterward existence arrested for gambling in 1875, Doc moved on with his friend Wyatt Earp, eventually landing in Tombstone, Arizona.

In the Span of a Single Lifetime, Dallas Gains and Loses a Great Streetcar System

When the Texas and Pacific Railway arrived in 1872, city leaders recognized a problem: in that location was no way to get residents through Dallas' dingy streets to the new railroad interchange. A streetcar system was proposed, and the Dallas City Railroad Visitor introduced 2 mule-driven streetcars, which ferried passengers back-and-forth up Main Street. One was named John Neely Bryan, after the metropolis founder, and the other was named Belle Swink, subsequently the daughter of the streetcar company possessor, Capt. George Swink.

Belle Swink lived to the ripe old age of 103. During her lifetime, she saw Dallas' streetcar system aggrandize into a sophisticated public transit network that included hundreds of miles of runway and stretched from the Hampton Hills neighborhood in Oak Cliff to the Lakewood State Order in Due east Dallas; from Mockingbird Lane in Highland Park to the Not bad Trinity Wood in South Dallas. By the time Swink died, in 1956, all the same, the streetcar that in one case bore her name was junked by metropolis leaders in favor of the car and an encroaching interstate highway system.

Forgotten Neighborhoods

The Heyday of the Jewish Cedars

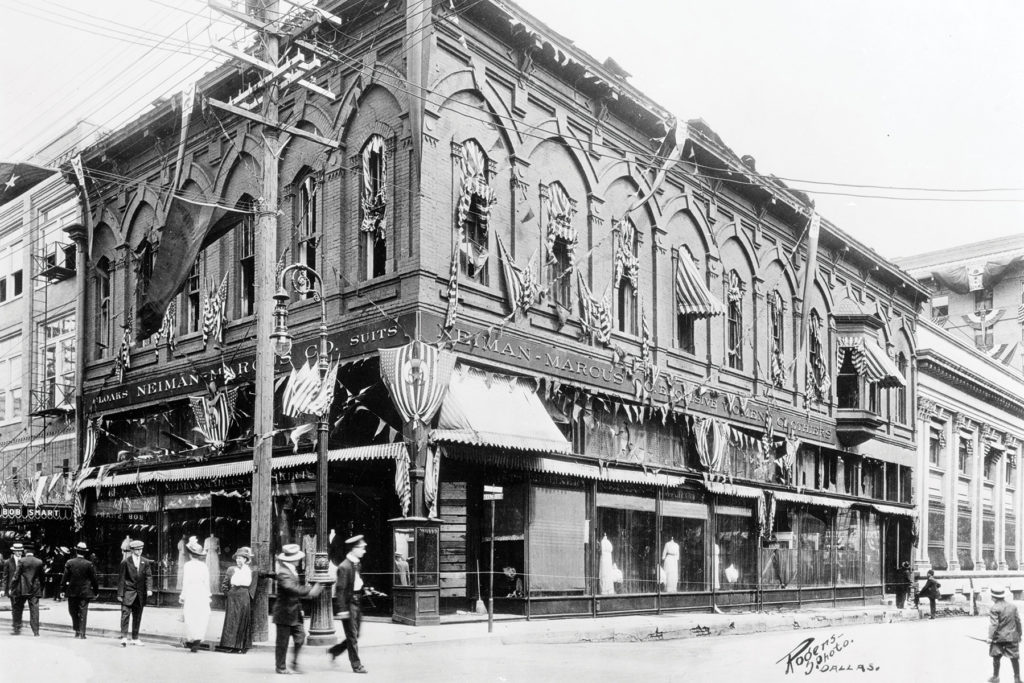

Herbert Marcus, Herbert'southward sis Carrie, and Carrie's married man A.L. Neiman had all worked for Dallas' two leading department stores—Sanger Brothers and A. Harris—when, in 1907, they opened the original Neiman Marcus at the corner of Elm and Tater. It was not a smashing fourth dimension to launch a high-end wear retailer. The Panic of 1907 had sunk the state into a depression, and both Herbert and Carrie were ill and missed the grand opening. Withal, Neiman Marcus would outlive its competitors.

Past the fourth dimension of this 1919 portrait of Mrs. Marcus and her iv sons (heir credible Stanley Marcus is continuing), the showtime Neiman's had burned downwards and the store had moved to its current location on Main Street. The Marcus family unit had also moved—to the burgeoning Cedars neighborhood, with its rows of Victorian mansions, red brick streets, and cast-iron storefronts. The Cedars was dwelling to Temple Emanu-El, the epicenter of Dallas' Jewish community. The temple was founded downtown in 1873, moved to a spot later on razed to brand way for I-30 in 1899, and migrated to South Boulevard and Harwood Street in 1916 before finally decamping for Due north Dallas in 1957.

Colonial Hill

Bordered by Pennsylvania Avenue on the n and Bannock Avenue on the south, between I-45 and U.S. Highway 175

In 1888, a neighborhood of bungalows and ii-story Colonial Revival houses formed along a new streetcar line running downwards Colonial Artery; easy access to transportation was the major selling point. Yet past 1907, wealthier residents began moving to Highland Park and Munger Place, equally they relied less on streetcars, architectural tastes changed, and the proximity to the industrial Trinity River area proved unpopular. Many of the original bungalows remain today, though some in disrepair.

Little United mexican states

Anchored past Pike Park, at ane signal information technology stretched from Oak Lawn to Ross Avenue

A Polish Jewish community gave way to thousands of immigrants fleeing the Mexican Revolution in the 1910s, and "Niggling Jerusalem" all but transformed into "El Barrio." The surface area was rich on culture—El Fenix started serving Tex-Mex there 100 years agone. Simply overpopulation led to impoverished conditions. By the end of the 20th century, all just a few remnants had been paved over past high-rises and highways.

La Réunion

Marker at tee No. 6 at Stevens Park Golf game Course, near N Hampton Road and Fort Worth Avenue

In 1855, Victor Considerant led 200 Europeans (more than half of the existing population of Dallas) to 2,000 acres due west of the city to establish a Utopian colony. They'd been told they could sail upwardly the Trinity River. Instead, they had to travel from Houston on horseback or human foot. The land they settled on was ill-suited to farming, and, in whatever case, they'd brought just 2 farmers with them. In a few years, the colony disbanded, with virtually of the families moving into Dallas proper. The Loupots, Santerres, Reverchons, and others became business organisation and cultural leaders.

Frogtown

East of the Due west End, running to Victory Park

Established by a 1910 city ordinance, Frogtown, aka the Reservation, was a cherry-red-light district where up of 400 prostitutes worked. The proper noun likely came from the frogs that could exist heard husky from a stream that fed the Trinity River. The women operated out of modest two-room "cribs," standing in open doorways to attract customers. Many of these buildings were endemic by leading citizens of Dallas, including Dr. Due west.W. Samuell, for whom a park, road, and high schoolhouse were named.

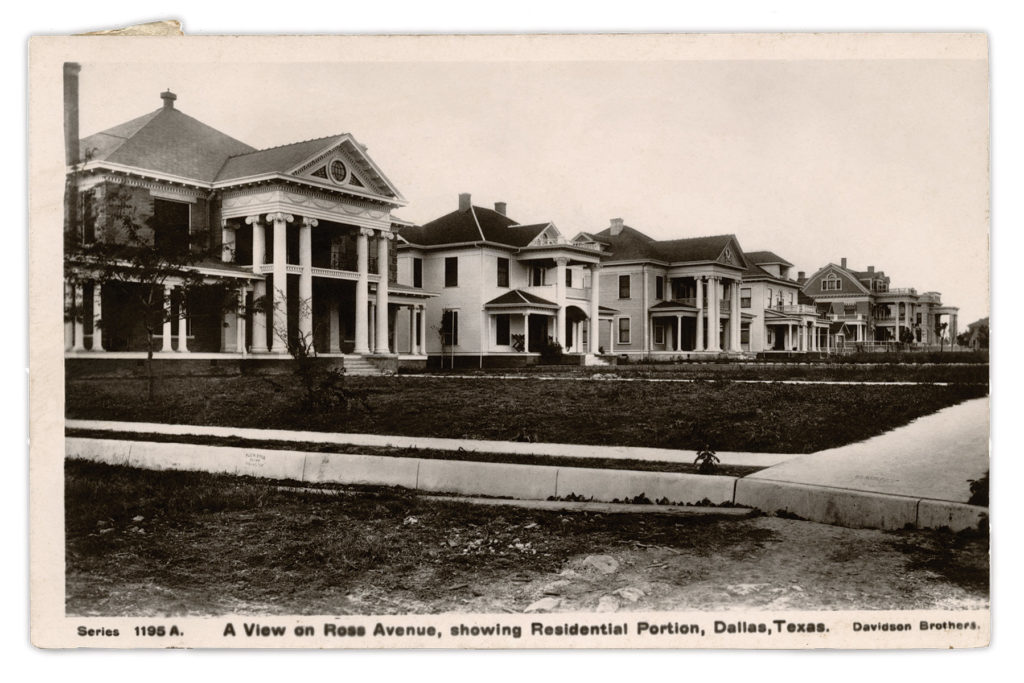

Dallas' Fifth Avenue

When New Yorker, Civil War vet, and Rattlesnake Oil salesman George T. Atkins moved to Dallas in 1876, just i address would suit an ambitious citizen of the fashionable frontier: Ross Avenue. Atkins moved into a big abode at the corner of St. Paul and Ross, function of a line of stately mansions that once stretched for more than than 2 miles, all the way to Greenville Artery. Sadly, almost none of the homes on "Dallas' Fifth Artery" survived.

Scyene

One-time Scyene Route and Belle Starr Drive, in what is now Pleasant Grove

This small-scale six-saloon town gained a bad reputation in the 1860s and '70s for being a dwelling house and refuge for several Missourian outlaws: Frank and Jesse James, the Younger brothers (i of whom fatally shot a Dallas deputy sent to arrest him), and Jim Reed, who ran away with a teenager named Myra Shirley—the woman later on immortalized in dime novels and Hollywood westerns equally Belle Starr, The Bandit Queen.

The Freedmen'due south Towns

Multiple locations

After the Civil War, hundreds of freed slaves moved to North Texas, setting upwardly numerous freedmen'due south towns, most of which have been destroyed by development or public works projects, or dismantled by forced segregation and gentrification. Some of these lost communities include North Freedmantown and Cord Town, which were located between Uptown and Deep Ellum; Fiddling Egypt, which was located just north of White Rock Lake; and Alpha, which was located northward of the Galleria Dallas.

Architecture

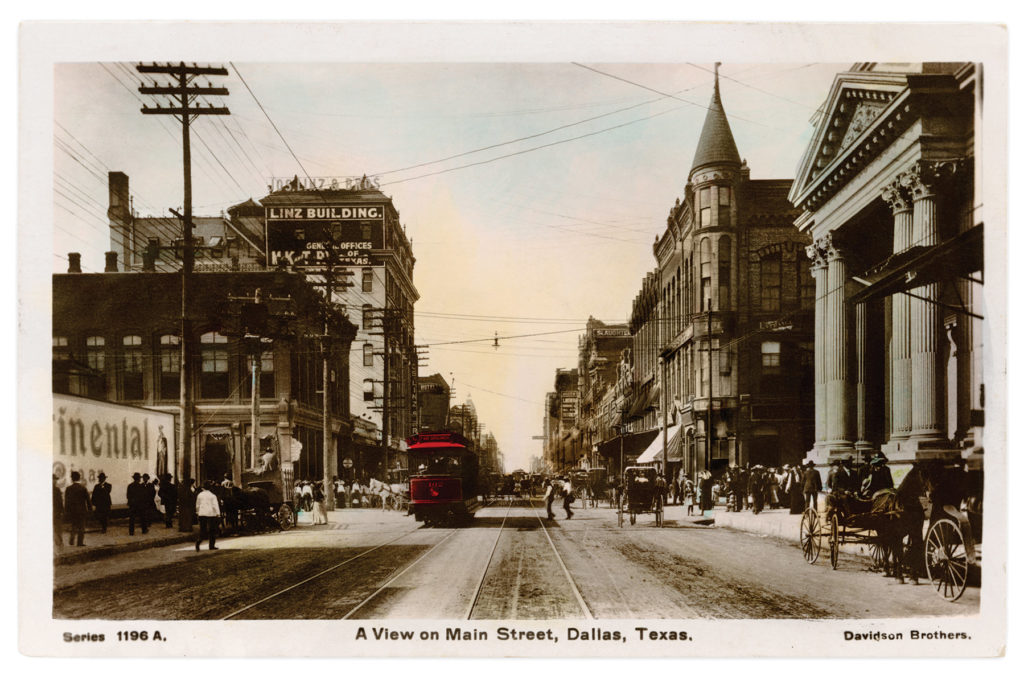

Chief Street In the early 1900s

This view of Master Street in 1908 looks e toward the Griffin Street intersection. In the foreground stands the stately Neoclassical façade of the City National Bank building, which was demolished in the 1960s to make way for 1 Main Place, Dallas' kickoff superblock development.

[image_grid id="ane″ /]

Praetorian Edifice

1607 Principal St.; now the Eye sculpture

Considered the starting time skyscraper in Texas, the xv-story, gold-ornamented Praetorian opened in 1909. It housed the Praetorian Order, a fraternal insurance company, until the building was stripped downwards to porcelain and steel in the early 1960s and became known every bit Rock Place Tower. The Joule owner Tim Headington dismantled it in 2013 to brand way for Twoscore 5 Ten and the 30-human foot-alpine Heart sculpture.

Dallas Times Herald Building

Bounded by Pacific Avenue, North Griffin Street, and Patterson Street, now a parking lot

The Dallas Daily Times-Herald was founded in 1888 when, to avoid closing their respective doors, the Dallas Daily Times and the Dallas Daily Herald decided to join forces. Owner Charles E. Gilbert was a prohibitionist and advocated a variety of causes, from immigrants' rights to improved sanitation. The Dallas Morning News later bought the paper and shut information technology down.

National Exchange Banking company Building

Main and Poydras streets, now Banking company of America Belfry

This Richardsonian Romanesque sandstone façade was home to the National Exchange Depository financial institution, founded by William H. Gaston and A.C. Camp in 1868. The bank would merge with others over time to become the Mercantile National Banking concern, and it somewhen vacated the edifice, which was demolished in 1940. Poydras Street was besides erased with the construction of the Bank of America Tower, and, in 2000, the Dallas City Council gave away the last segment of the street to McDonald'south for a drive-thru.

[image_grid id="ii″ /]

The Oriental Hotel

208 Due south. Akard St.; now Whitacre Tower

Missouri real manor developer Thomas Field purchased the plot of land in 1887; six years after, he opened the $500,000 Oriental Hotel. Finished with Italian marble, outfitted with mahogany, and topped with a Moorish dome, the modernistic structure was completely electric. It was torn down in 1924, and the Baker Hotel took its place.

Federal Post Function

1700 Main St.; now the Mercantile National Bank Building

The gingerbread-style Federal Post Office building was constructed in 1889 with an impressive clock belfry. But later on it was abandoned 47 years later, the city accounted it a liability and razed the structure. The current U.S. Postal service Office and Courthouse building sits five blocks to the north.

[image_grid id="3″ /]

Renaissance Revival City Hall

1321 Commerce St.; now the Adolphus Hotel

Dallas' third city hall building opened in 1889, a few blocks east of its previous location. The Renaissance Revival compages—with its stonework, arches, and ornate details—resembled a castle. Beer mogul Adolphus Busch bought the land in 1910 and demolished the structure so he could build his namesake luxury hotel, where City Hall Bistro now pays tribute to the former seat of government.

Baker Hotel

208 Due south. Akard St.; now Whitacre Tower

After its opening in 1925, the Baker Hotel became the center of the city'south social scene. Tommy Dorsey played at the Peacock Terrace with its lily pond and live ducks, debutantes danced in the Crystal Ballroom, and Lawrence Welk performed for lunchtime guests in the basement restaurant. The hotel was imploded in 1980 to make room for the Southwestern Bong Telephone headquarters.

[image_grid id="four″ /]

Ursuline Academy of Dallas

Bounded by Live Oak, St. Joseph, and Bryan streets, and North Haskell Avenue; at present the Dallas Theological Seminary parking lot

In 1874, six Ursuline nuns from Galveston established a Catholic school in a downtown Dallas cottage. A decade later, students moved to a 10-acre Neo-Gothic building in East Dallas designed by Nicholas Clayton. The structure was demolished in 1949, and Ursuline, the city's oldest continuously operating school, moved to its electric current Preston Hollow site.

Marsalis Sanitarium

Southwest corner of North Marsalis Avenue and Due east Colorado Boulevard; now A Time & A Season Christian Daycare

Downwards the street from Lake Cliff Park in Oak Cliff, this pink-hued architectural landmark was congenital by programmer Thomas Marsalis in 1889 for $65,000. Information technology was later sold at a public auction in 1903 to Dr. J.H. Reuss, who opened it as a 15-bed individual surgical hospital in 1905. Nine years afterwards, information technology was destroyed in an oil fire.

[image_grid id="v″ /]

Sanger Brothers Department Store

303 N. Akard St.; now Dart Akard Station

The Dallas outpost of this successful Texas dry goods chain opened in 1872 and was operated by Philip and Alexander Sanger, brothers from a family of pre-Civil State of war German immigrants. It would afterward move to an viii-story building at Main and Lamar streets, which is now part of El Centro College.

Dallas Club

South Poydras Street at Commerce Street; at present a parking lot

Designed by the Dallas architecture business firm of Stewart and Fuller in 1888, this private gentlemen'southward social club was demolished in 1920.

Allen Brooks and the Elks Arch

In 1908, an arch spanning the intersection of Main and Akard streets was erected to celebrate the National Convention of the Fraternal Lodge of the Elks. In 1910, it became the setting of the last lynching in Dallas County.

Allen Brooks was a 65-yr-old African-American laborer who was defendant of raping a child. In the subsequent days, newspapers carried sensational (and spurious) accounts of the incident. When Brooks was taken to the courthouse for his arraignment, a massive crowd gathered outside.

In a urban center where politics was nonetheless dominated past the Ku Klux Klan, the crowd was thirsty for swift vengeance. They broke into the courthouse, seized Brooks, tied a rope effectually him, and lowered the man out a 2d-story window. A cry rang out: "Take him to the curvation!" Brooks was dragged down the street and hanged to die from a telephone pole near the Elks Arch's welcome sign.

A photograph of the horrific event was turned into a postcard, a not uncommon practice at the fourth dimension to peddle the murder of African-Americans every bit popular amusement. Later, when the Southwestern Life Insurance visitor needed to complete sewer work under the curvation, the City Council had it quietly removed.

[image_grid id="six″ /]

Sanger Library

South Harwood Street and Park Row Avenue; now a vacant lot

The Sanger brothers built this co-operative in 1932, at a cost of nearly $45,000, to serve the Jewish community in the growing Edgewood add-on. Architect Henry Coke Knight designed the Georgian Revival building with its French-inspired slate mansard roof.

Dallas Cotton Exchange Edifice

Southwest corner of North St. Paul and San Jacinto streets; at present Commencement Baptist Dallas

Built in 1926 at a cost of $1.5 meg, this was a 17-story reminder of the metropolis'south prominence as the world'south largest inland cotton market. In an attempt to modernize the façade in the 1960s, it was covered with concrete panels. The building was imploded in 1994 when redevelopment plans failed to materialize. Its signature stone lions at present grace The Stoneleigh Hotel entrance.

Nightlife

Deep Ellum Blues

As Dallas emerged as the largest inland cotton market in the world, the area around the Houston and Texas Cardinal Railway began to attract laborers from the surrounding countryside. Many were African-Americans, and in the segregated, often racially tearing metropolis, they found refuge along the so-called Central Track, setting upward businesses, shops, theaters, and clubs that would go the eye of Dallas' cultural heritage.

Those country-born migrant workers included bluesmen Blind Lemon Jefferson and Blind Willie Johnson, folk and blues pioneer Huddie William "Atomic number 82 Abdomen" Ledbetter, blues pianist Alex Moore, and Charlie Parker mentor Henry Franklin "Buster" Smith. Robert Johnson came through Dallas to record his famous sessions at nearby 508 Park. In those early days, information technology was non uncommon to meet a young T-Bone Walker leading Blind Lemon up and down Fundamental Track and dancing for spare change on the streets.

If you desire to meet the real heart of Deep Ellum, you lot'll have to stand under I-345, the elevated highway that was built directly through the freedmen'southward towns of Due north Dallas, Stringtown, and Deep Ellum, demolishing institutions similar the Harlem Theatre and Gypsy Tea Room.

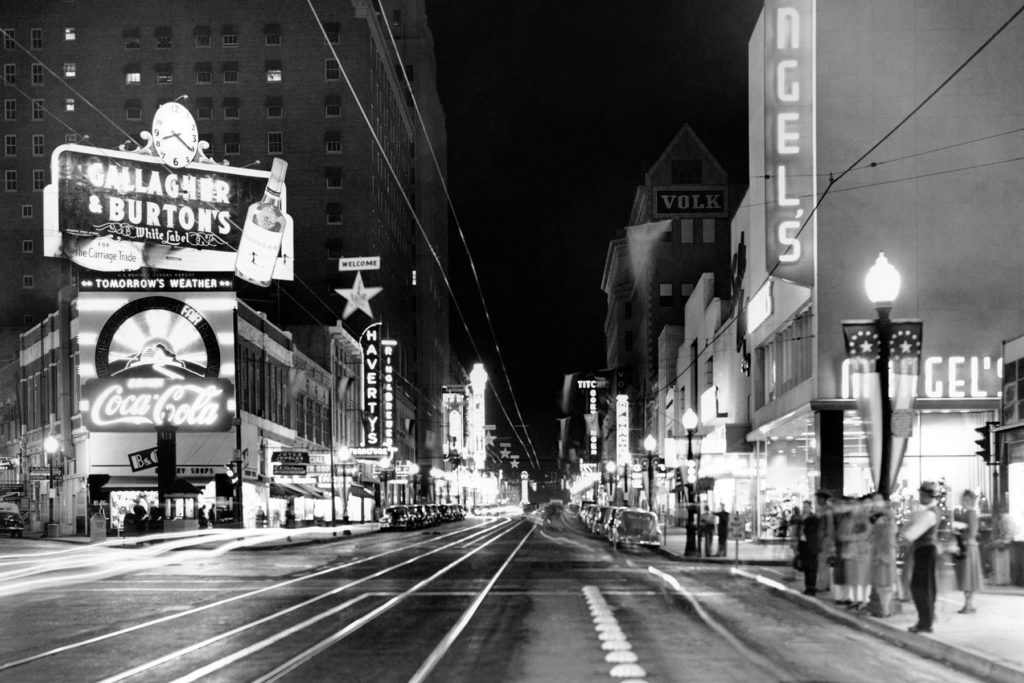

Elm Street'south Tinsel Town

In 1905, a 26-year-old St. Louis transplant named Karl Hoblitzelle opened a vaudeville phase located at the corner of Commerce and St. Paul streets called the Majestic. By 1921, Hoblitzelle's Regal would move to Elm Street and become a movie house. Information technology joined a overabundance of theaters popping up along Elm—spectacularly lit and ornate movie palaces with names similar the Capitol, the Rialto, the Washington, and the Capri. The Queen, for example, was decked out in nude statuary and plaster reliefs depicting historical queens and boasted a "drinking glass-and-silverish screen." Past the 1940s, Elm Street boasted more movie theaters than any other street in the country save Broadway.

Hoblitzelle expanded his Interstate Amusement Visitor, which started equally a vaudeville booking agency, into a movie theatre and distribution powerhouse, introducing innovations like air-conditioning. He as well became a leading civic figure, serving on numerous philanthropic boards and helping to found the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. As for the theaters, sadly, only his Majestic has survived.

Dallas Was on Ray Charles' Mind

The Sounds of Two Cities

Strictly enforced Jim Crow laws ensured the emergence of two distinct cultural worlds. In the 1930s, D.F. Powell opened the elegant brick Powell Hotel at 3115 State St. Information technology was the first African-American-owned hotel in Dallas and one of the few places African-Americans could stay. Joe Louis, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Fats Waller all stayed there. William Sidney Pittman, who designed Knights of Pythias Hall in Deep Ellum, lived there until his expiry in 1958.

In 1942, the Rose Ballroom opened nearby at the corner of Hall and Ross, when Primal Superhighway did non nevertheless subdivide the neighborhood. Blues guitarist Freddie Rex's daughter Wanda called the pocket-sized venue "simply a little blackness gild, a joint," simply it hosted a who's who of local and touring talent: T-Bone Walker, Large Joe Turner, Pee Wee Crayton, Henry Franklin "Buster" Smith, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, Lionel Hampton, and more. Operating until 1975, it was known intermittently as the Rose Room, Empire Room, and Ascot Room. When white audiences wanted to see acts at the club, they would take to look for "whites-merely nights," since mixing the races would take but invited a police force raid.

Dallas' Other Blues Legend

Zuzu Bollin was lost, constitute, and at present he's lost again. The bluesman, who grew upwardly in Frisco next door to a juke joint, recorded ii 78s in the 1950s, including the jump blues classic "Why Don't You Swallow Where You Slept Last Nighttime" (featuring futurity Ray Charles sideman David "Fathead" Newman on sax). Simply the ascension of rock and scroll slowed his career and the merger of the blackness musicians' spousal relationship with the all-white Local 147 all merely killed it. He spent the '60s, '70s, and almost of the '80s broke and in obscurity, until Chuck Nevitt, founder of the Dallas Blues Guild, found him and released Zuzu Bollin: Texas Bluesman, in 1989. Bollin was able to tour Europe and play Holland's big-deal Blues Estafette before he died of cancer in 1990. His name has faded abroad over again since and so, overshadowed by T-Bone Walker and Blind Lemon Jefferson. But he deserves mention in their company.

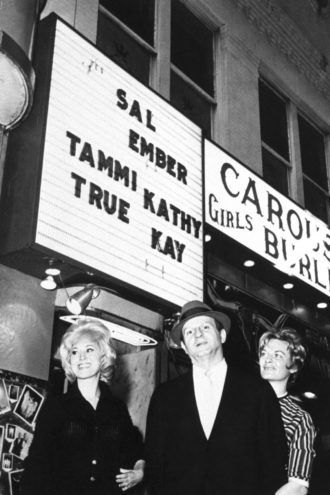

The Granddaddy of Dallas Gentlemen's Clubs

C.A. "Pappy" Dolsen opened his kickoff club, La Boheme, in 1924. In the 1930s, he went into concern with notorious gambler and bootlegger Benny Binion. It was after the war, however, when Pappy opened the grande matriarch of Dallas burlesque joints, Pappy's Showland, which was located on the other side of the Commerce Street Bridge in West Dallas.

It was not enough to call Pappy's Showland a strip club. Burlesque dancers shared the stage with singers, tap dancers, boxers, full orchestras, and some of the near popular entertainers of the day. Tommy Dorsey'south orchestra played Pappy's, as did Bob Hope. And Pappy'southward deep connections with politicians—and the local underworld—enabled him to stay open long past when liquor laws immune. But that all came to an end when Oak Cliff and W Dallas banned alcohol sales in the mid-1950s. Pappy'south Showland closed up shop.

That didn't cease its namesake. The charismatic showman, who once called Jack Ruby a "double-crosser" and boasted to Texas Monthly that he could tell how much a dancer would make later watching her for one minute, continued to manage dancers well into the 1970s. He chewed cigars with his tobacco-stained teeth and kept runway of his talent in a niggling black book, booking strippers at 4 clubs and operating out of a little bungalow nearly Dallas Honey Field.

The King of Small Time

Earlier his engagement with Lee Harvey Oswald, Jack Ruby lorded over a considerable subsection of Dallas nightlife. He endemic the Vegas Social club on Oak Lawn Avenue, Hernando'southward Hideaway on Greenville Avenue, the Silvery Spur on Ervay Street in the Cedars, and Bob Wills' Ranch House, which was after renamed the Longhorn Ballroom. The center of his small empire was the Carousel Social club, which served upwardly strippers, champagne, and pizza, and was located side by side to Abe Weinstein's Colony Club on Commerce Street, beyond from the Adolphus Hotel.

All these stages gave Crimson considerable influence over the careers of musicians who passed through his clubs. David "Fathead" Newman—Ray Charles' saxophone thespian and a regular performer at the Vegas Social club and Argent Spur—said Cherry wouldn't allow African-American musicians to look at his white female person dancers. Bluesman Zuzu Bollin said a spat with Cerise over booking fees resulted in the club owner pulling Bollin's records off local radio. But there was one performer Ruddy couldn't nab. After headlining the Big D Jamboree at the Sportatorium, a twentysomething Elvis Presley opted to play an afterparty at the Round-Up, another Cedars guild just up the block from Ruby's Silverish Spur.

Sports

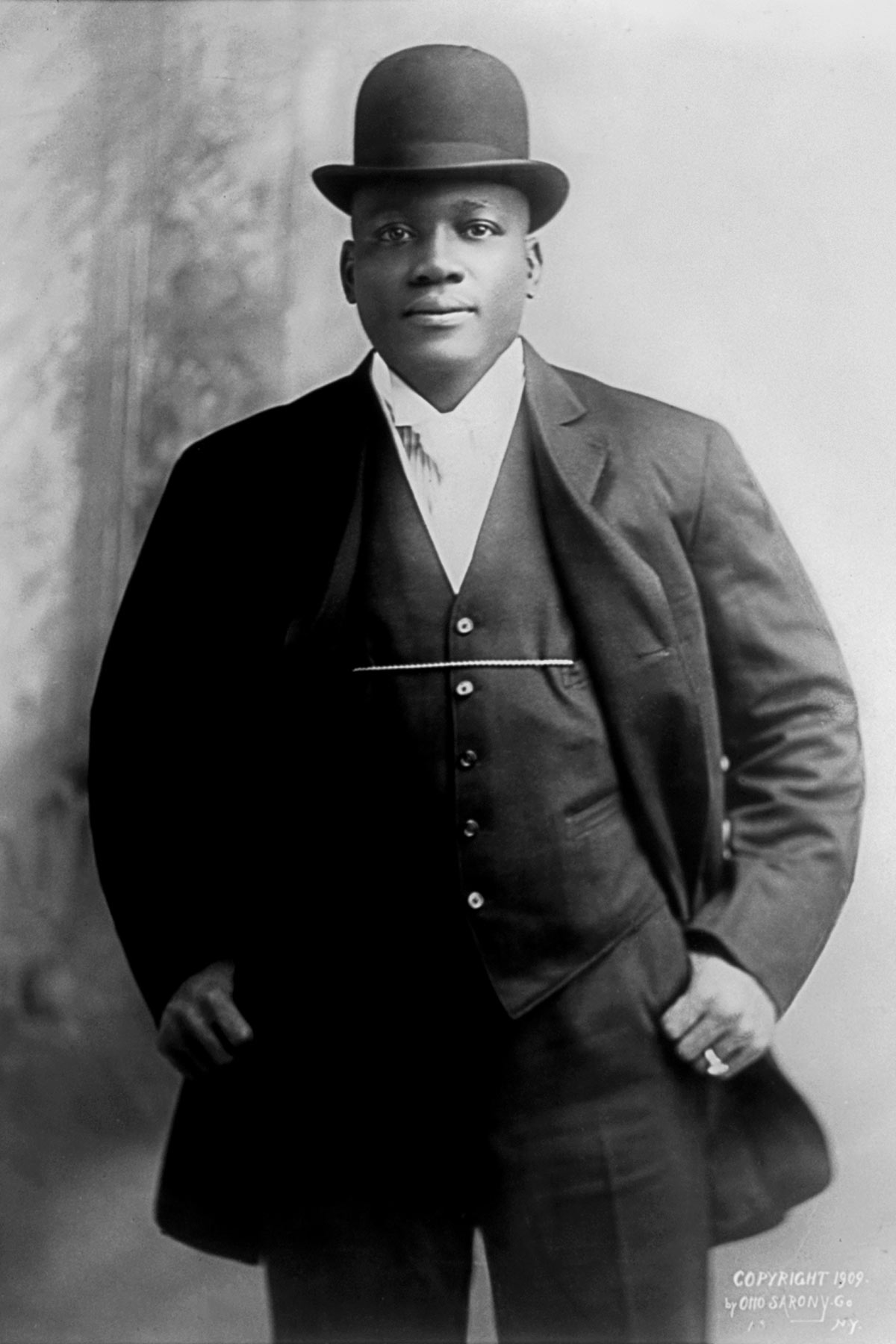

Jack Johnson

Before he became heavyweight champion of the world and an inspiration for Muhammad Ali, Jack Johnson (seen here in 1909) was a high schoolhouse dropout living in Dallas, working at a racetrack, exercising horses. It was in Dallas where Johnson would meet Walter Lewis, the trainer who convinced Johnson to put on the gloves and prepare off on a journey toward greatness.

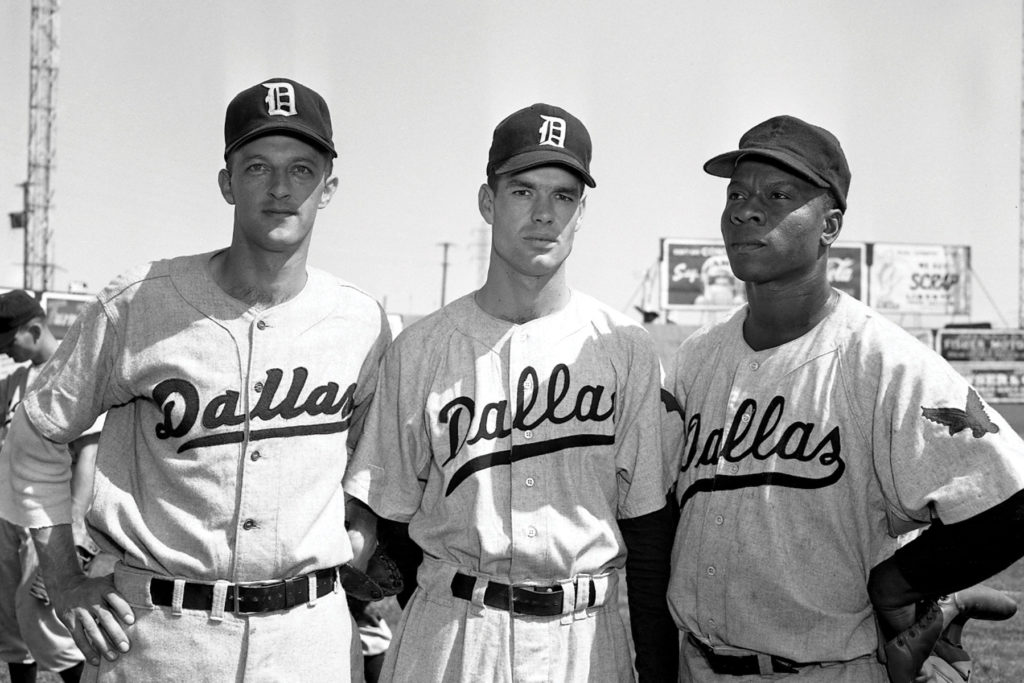

Baseball Town, Texas

Dallas hosted its first football game game in 1891—on Thanksgiving, fittingly. At the time, though, Dallas was a baseball town. Texas League games were played on fields well-nigh Off-white Park and the Dallas Zoo. In 1915, Gardner Park opened on a barefaced overlooking the Trinity River in Oak Cliff, and, later a burn down, information technology was replaced by Burnett Field in 1924. Burnett Field was home to a number of teams that played in the Texas League and hosted exhibitions that brought players such as Willie Mays to town. Dallas' Negro League teams had to play at Riverside Park, which stood a few blocks away. Information technology was there that the Dallas Blackness Giants fielded a young Booker T. Washington High School graduate named Ernie Banks, who would go on to play for the Kansas City Monarchs and get a Hall of Famer with the Chicago Cubs.

Burnett Field finally airtight in 1964, afterward baseball moved west to the newly opened Arlington Stadium. But before that, in 1960, Burnett hosted i more team, serving every bit the practice facility for the Dallas Cowboys' first season.

Leisure

Dallas' Times Square

For decades, the intersection of Elm and Alive Oak at Ervay bore a bright neon Coca-Cola sign that displayed the weather forecast and announced the eastern entrance to Elm Street's famed theater row. Streetcars snaked through the interchange, and moviegoers could snack at nearby restaurants and cafes, like the Mayflower Coffee Store, United mexican states City Cafe, and Stagecoach Inn. When the site was cleared for the construction of the 1700 Pacific skyscraper in 1983, the portion of Live Oak that intersected with Elm was ceded to the development.

Mayer'due south Garden

Located at the corner of Elm Street and Rock Place was one of Dallas' first beer gardens. Mayer's featured a small zoo and installed the city's get-go outdoor electric lights. In Dallas' early on days, saloons, beer gardens, and breweries did brisk business organization. By 1917, there were about 183 confined in boondocks. However, after the canton passed a local option on Prohibition in Oct of that twelvemonth (a resolution not supported by the metropolis but carried through past the surrounding communities), the number of bars dropped to zero.

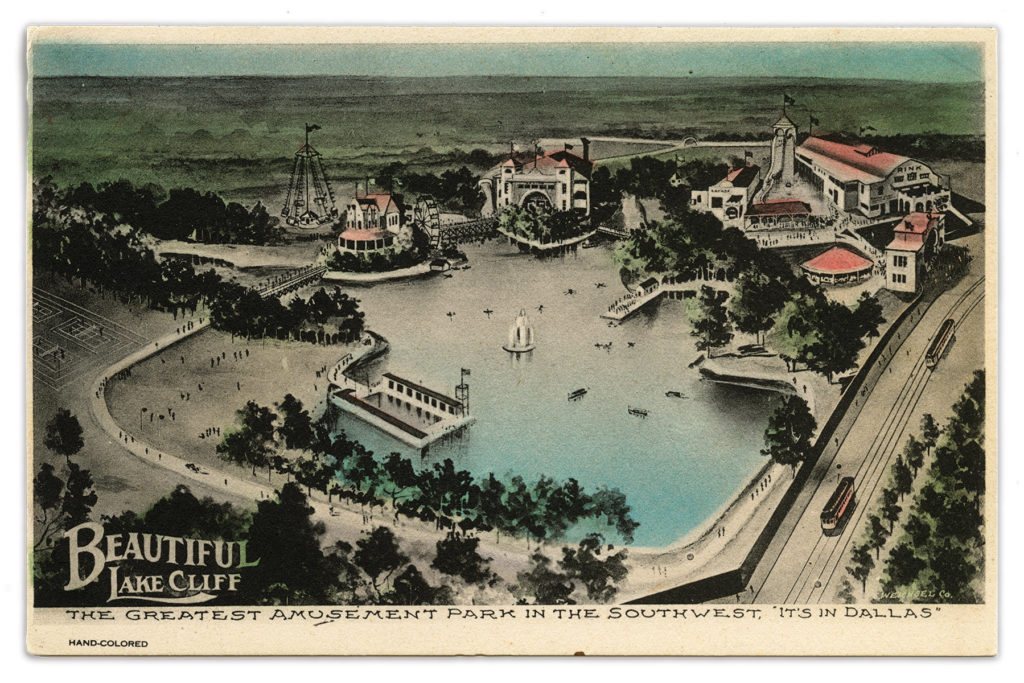

The Coney Isle of the Southwest

From 1906 to 1913, Oak Cliff was home to an amusement park that, according to its founders, outdid Coney Isle. Lake Cliff Park featured a 2,500-seat theater, an eighteen,000-foursquare-human foot roller-skating rink, a roller coaster, Japanese village, mechanical swings, and water rides. Dallasites could take a rail link straight to its front door and marvel at the park's electrical lighting. Today, visitors can still spy remnants of the brick-lined aqueduct.

The Trinity Bridge Jumpers

On Dominicus, March 21, 1897, a crowd of 6,000 people converged on the Commerce Street Span to watch a high-diving exhibition past a man named J.B. Wilson who had pledged to dive 65 feet, headfirst, from the top of the span, into the pelting-swollen Trinity River.

Just before it was fourth dimension to spring, Wilson appear that monetary contributions were necessary before he would brainstorm. The crowd'due south mood soured. Afterward an 60 minutes of walking through the unamused crowd with a collection box, Wilson'southward take was a mere $xiii. Unhappy, he informed the crowd that the payment was not enough to warrant a 65-human foot dive—instead, he would leap from the lowest function of the bridge, about 35 feet. The crowd jeered, and his swoop was met with icy silence.

So, standing on the highest point of the bridge, a cocky 22-year-one-time shouted to Wilson, "Y'all're not the merely turtle in the tank!" Before anyone realized what was happening, he tore off his glaze and jumped feet-get-go into the river. The stunned crowd erupted in cheers, and Curvation Sexton, a local candy-maker, became the unexpected hero of the hour.

Wilson, damp and upstaged, left town quietly, and immature Sexton reveled in his cursory fame as Dallas' "world champion" Trinity Bridge Jumper (a title which, equally far equally nosotros know, however stands). —Paula Bosse

Read More

Society

Fashion Face up-off

On October xiii, 1884, the Idlewild Club debuted its first immature women at a trip the light fantastic toe on Commerce and Lamar; and past the 1890s, the Terpsichorean Social club was added to the debutante flavour. Only perhaps there was no better evidence of how well-regarded Dallas' societal reputation had go than the fact that, in 1891, Bertha Honoré Palmer, a leader of Chicago'due south fashion world, decided to make a trip to Dallas as part of her preparations for a style exhibition at the Globe'southward Columbian Exposition.

The ladies who lunch were silly at the news, and they took care to ensure that their honored guest was properly received. Mrs. Alfred Davis was chosen to head the welcoming committee. Mrs. Davis had come to Dallas from Kentucky, married a wealthy wholesale grocery owner, and was known for her bold style, such as wearing rings on the outside of her gloves. According to John William Rogers' The Lusty Texans of Dallas, the Davises were rumored to possess a "quart of jewels," and they were the merely couple in town who spent their summers in France.

The luncheon for Mrs. Palmer was advisedly planned. Potted palms were brought in; the card included chicken salad made simply with white meat. A mannerly little girl was called to present Mrs. Palmer with a bouquet of American Dazzler roses, whose stems were almost every bit tall as the girl. And Mrs. Davis knew precisely the dress to wear: a blackness panne velvet, satin, and lace gown with a long train that was designed by a famous Paris couturier.

When the day came, and Mrs. Palmer finally arrived, she was greeted at the door by Mrs. Davis. The guests stood aghast. It was an unthinkable faux pas. Both women were wearing the same dress.

A Guide to Not-Quite-Lost Dallas

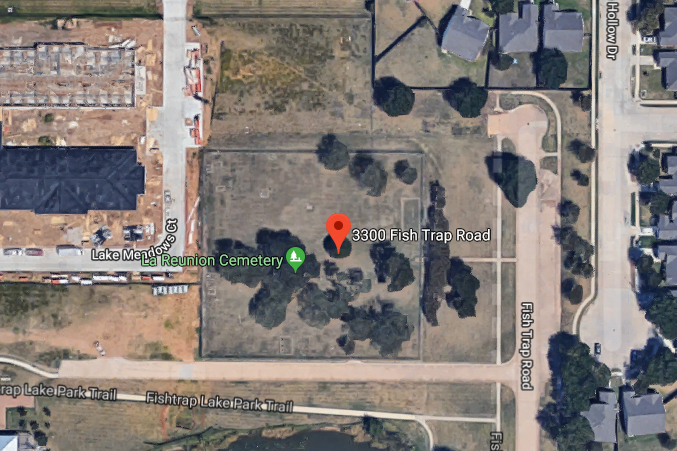

La Réunion Cemetery

rn3300 Fish Trap Rd.rnrnFrom 1855 to 1858, French, Swiss, and Belgian pioneers known every bit La Réunion established a Utopian colony near the Trinity River in what is now West Dallas. Their remains can be found in a 1.3-acre cemetery at the due north end of Fish Trap Lake. Among the markers is one for botanist Julien Reverchon, whose larger legacy is his eponymous park along Turtle Creek.

Martyr'south Park

rnJust northward of where Elm, Commerce, and Main streets meetrnrnNot far from the section of Elm Street where Kennedy was assassinated sits a simple half-acre enclosure of grass and trees. This small park marks the spot where three slaves were hanged for allegedly starting the 1860 fire that destroyed downtown. Without a trial—and in spite of prove of careless smokers and 3-digit July temperatures—Patrick Jennings, Samuel Smith, and a man identified as Old Cato were murdered. No sign or marker cues passersby to the tragic importance of this spot.

Cumberland Hill School

rn1901 Northward. Akard St.rnrnThe only surviving school edifice from the 1800s, Cumberland Hill School was designed by A.B. Bristol and constructed in 1888. The elementary school closed its doors in 1958, but former Gov. William P. Clements Jr. bought the building in 1970 and remodeled information technology, turning information technology into the headquarters of SEDCO, an oil drilling company. It is now a multipurpose office space.

508 Park

rn508 Park Ave.rnrnBuilt by Warner Bros. Pictures in 1929 when they were trying to incorporate sound into their films, this art deco building became rich with music. Tenants such every bit Brunswick and Decca Records shared the space over the years, and artists from Robert Johnson to Eric Clapton would record on the third flooring. The edifice is now part of the Encore Park projection, which includes an outdoor amphitheater and the Museum of Street Culture. The original Warner Bros. sign has been restored on the side of the building.

Mrs. Hargrave's Cafe

rn3308 Swiss Cir.rnrnBefore meeting her soul mate and literal partner in crime, the infamous Bonnie Parker worked at this cafe as a waitress. The name was actually Mrs. Hartgrave's, but it is oft misspelled in historical chronicles. As of 2015, at that place were plans to turn the derelict building across from Baylor Academy Medical Center into a new restaurant.

The Hord Log Cabin

rn2804 South. Cockrell Loma Rd.rnrnThis tiny motel built past Guess William H. Hord in 1845 was the first permanent structure to go up due west of the Trinity River. Charlotte and Martin Weiss saved the cabin from demolition by donating it to American Legion Post No. 275 in 1942.

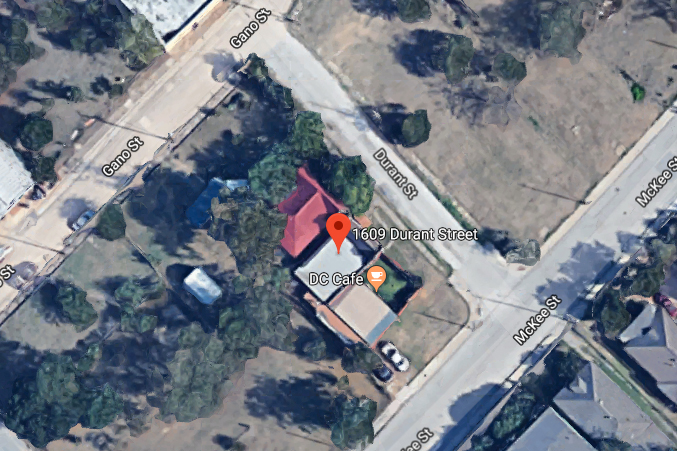

1609 Durant St.

rnOne of the oldest houses in Dallas can be constitute at the corner of Durant and McKee. Built in 1884, this brick cottage used to be the telephone hub of the Cedars neighborhood. Information technology is now a private abode.

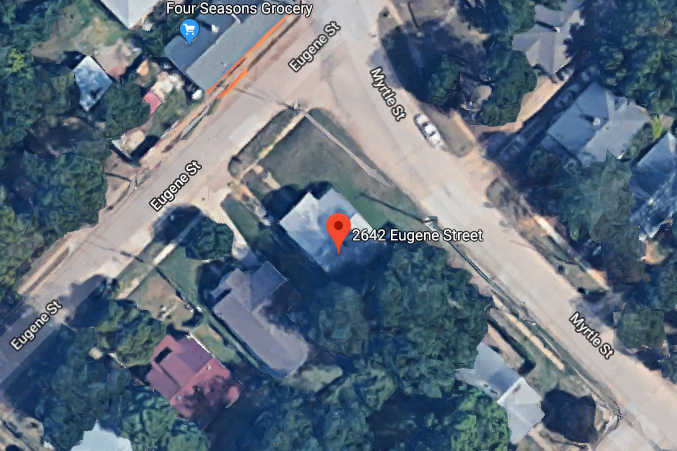

Ray Charles' Business firm

rn2642 Eugene St.rnrnIn this now ramshackle gray and white bungalow in South Dallas, pianist and songwriter Ray Charles composed music for three crucial years of his life in the mid-1950s. He moved to Dallas from Seattle to marry his girlfriend at the fourth dimension, Della Beatrice Howard, who was pregnant with their first child and living in the Greenish Acres Cabin. He refined his sound just down the street: at the Empire Ballroom, American Woodman Hall, and Arandas Club.

mastersonphou1986.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.dmagazine.com/publications/d-magazine/2018/march/lost-dallas-history-secrets/

0 Response to "Name of Company Selling Metal Yard Art at Texas State Fair"

Postar um comentário